From standard writing pain to reproducible paper

When I wrote my very first paper the process was an insightful struggle. I pretty much right-away accepted most of the things that made it hard as “inevitable”:

- Spending hours in writing block staring at an empty page.

- The manuscript ping-pong between me and my supervisor - I tended to spend a week writing or rewriting in the Word document, then I would sent it to my supervisor, and he would write, and each of us had to take a break in writing for the time the other one worked on it.

- The organization effort of planning who would address which review comment in the manuscript, such that we could work in parallel without ending up editing the same text.

- Hours of copying and checking endless correlation tables from SPSS outputs decimal point by decimal point into the manuscript, and redoing it when we included other measure after the review.

- The sad process that turned the enthusiasm of writing up and sharing a scientific project for the first time (it was my Bachelor’s thesis) to the fed up feeling of “ugh, God, I can’t wait to have this out of sight” and the creeping insecurity whether the results are 100% correct after many chaotic changes to the manuscript and analysis (which was point-and-click-in-SPSS) that greatly contributed to the latter feeling.

While I haven’t found an effective cure against the writer’s blocks, it was a revelation when my Master’s thesis supervisor finally showed me how to eradicate all of the other struggles completely and taught me how to write a dynamically generated, reproducible scientific manuscript collaboratively. I had never been more proud of a manuscript, never been more confident in my results, and never experienced a more effective writing process.

This way of writing has become my default, and I can whole-heartily recommend to everyone. I know from a first-hand experience that it is not straightforward how to not only share code and data easily, but also allow others to build your complete scientific manuscript from scratch. I wouldn’t even have thought about this if Michael hadn’t explained this concept to me. But dynamic document generation is easy once you know how. And beyond being easy, it also makes your science more transparent and extensible, it increases your own trust in your results and it saves you time.

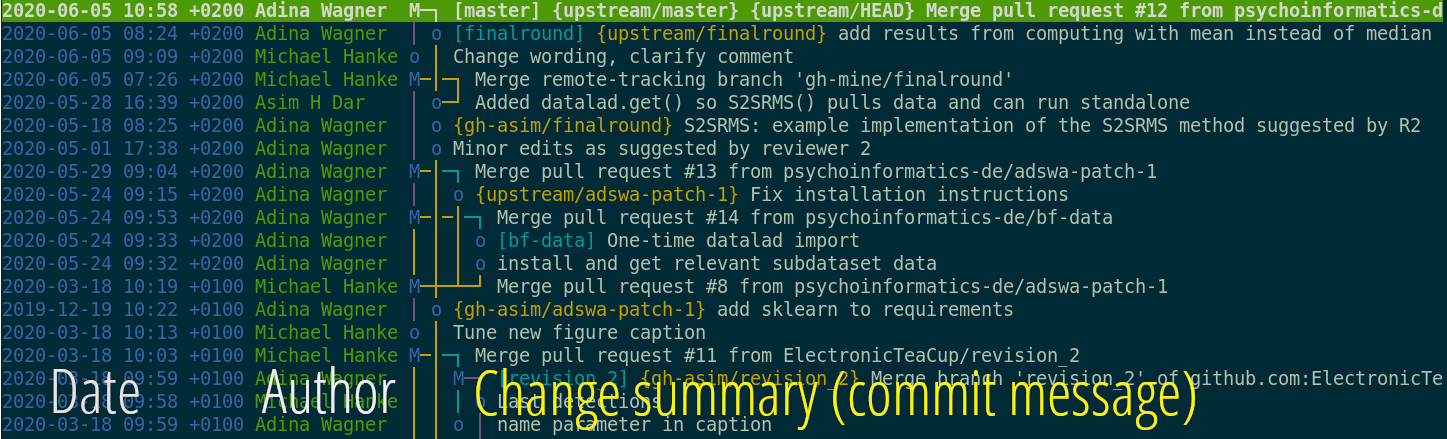

To help others get started, I have shared how I wrote my very first reproducible, dynamically generated manuscript in talks and in a detailed write-up in the DataLad Handbook. For the paper, me and my co-authors have used Git for version control and collaborative writing, DataLad to share and link code and data via GitHub, LaTeX to embed dynamically generated results and figures, and Makefiles to orchestrate code execution and manuscript compiling. In the end, we the result is a publicly shared GitHub repository that allows a complete recomputation and manuscript regeneration with a single command: github.com/psychoinformatics-de/paper-remodnav.

Most of the tools used for this were new to me. I was a new and only self-taught Git user. Many years back I had taken a LaTeX course in University, pretty much out of boredom and for fun, but it was for Mathematicians and mainly taught me how to use it to typeset impressive formulas. In previous years, neither of my universities ever allowed me to submit work in LaTeX (seriously), and so my LaTeX-foo was really weak. I had honestly never even heard of Makefiles before. And starting with DataLad as a complete newbie was so painful it greatly contributed to the decisions that led to writing the DataLad Handbook. But: In the end it worked. Really well.

Writing and coding took place in conjunction, out in the open, and in close collaboration, even though all authors of this paper worked on it remotely, at one point on two different continents. Manuscript and analysis decision weren’t made over email, but via GitHub issue. Because the manuscript was dynamically generated, and results were embedded automatically, without hand-copying tables, it was only a single make command that recomputed all results and updated the manuscript when I discovered an error in the input data and fixed it. Analysis code was checked by everyone involved and publicly available, just as the data - even if I (as a code newbie clinical psych student) was unsure about whether my code was 100% correct, I drew immense confidence from the fact that everyone you run my code, reproduce my code, and comment on errors or suggest improvements.

The tools we combined and used demonstrates one way of doing this. But there are many more, and a large number of tools exist to make the process even easier. Here for example is a great tutorial on how to do it with R MarkDown. Regardless of how you write your reproducible paper, it will improve your science and workflows. Goodbye Word-Doc ping pong, goodbye mistrusting my own results - hello open and reproducible science! I won’t go back :)

comments powered by Disqus